A City Seen

“Cities […] are as alive, as feeling, as fickle and uncertain as people.” - Roman Payne

What is in the city? How does one find a city? This is to ask, how might an artist document their urban environment?

With the advent of post-industrial growth in the United Kingdom came the great industrial Metropolis, and with it, all the new, modern technologies. Suddenly, the quickly changing world offered a new avenue to see it: through a viewfinder, through a lens. The camera allowed for truthful retellings of the city, offering to history an authentic guide through a city’s streets.

This trend of urban photographic documentary continues on and is most prevalent today whereby everyone with a smartphone is a photographer. With this democratised medium to record the world, we are all encouraged to utilise our individual perspectives to document our environments. Yet, can this objective process speak truly of our own attitudes and values? How and why might we inform our own approaches to documenting our environments?

“I like the factual nature of photography, the immediacy, but it’s not enough. Paint is more emotional.” - Tim Garner

There is more to the process of seeing the city than simply observing it. Finding the tonal qualities of an urban space requires an emotional connection with it, whether this relationship is sustaining or straining, because the city possesses its own character that cannot justly be captured onto celluloid.

A city is a place of sensorial bombardment, that must be searched through and interrogated to comprehend. To understand the emotional qualities of a space, one must go further still and employ an empathic analysis.

For an urbanist to find the character of the urban space is also to confront their own identity. Trying to understand a place is a process of self-recognition, of one’s attitudes towards the space, to discover what one might already know about their environment. In an autographic approach, we accrue personal significance from artistic works: in looking to see and know a place is to imbue a piece of work with meaningful identifiers of the self.

There are many ways an urbanist painter might employ in their works these identifiers, whether through a careful selection of colour, by creating a dramatic tone through their stylisation, or even through the textures and materials utilised across the canvas.

Colour

A pioneer of the urban landscapes who understood this line of inquiry into finding 'the cityscape' was the Manchester-residing French painter, Pierre Adolphe Valette (1876-1942). With his impressionist style, Valette finds in his works a fogged looking-glass into the smoking skies of the emerging Edwardian city, capturing tender moments of the ethereal streets to produce studies of the industrial sunrise.

Valette’s uniquely delicate reception of the city scene is transposed into this delicately stylised depiction. The scene is established in "Rooftops, Manchester" in employing a quiet, soft palette, with cool muted blue rooftops and washed out pastel skies, to tell of Valette’s gentler relationship to the city. There is warmth in these pale ochre undertones that sees through a misty skyline, drawing attention to the hearth of home to which the muddled mix of commuters are returning.

Tone

As a student of Valette, L. S. Lowry (1887-1976) furthers the study of the city with his playful approach. He talked of his “ambition […] to put the industrial scene on the map” by focusing on those typically less compelling features of twentieth century industrial progress.

“The mill was turning out hundreds of little, pinched figures, heads bent down… I watched this scene — which I’d looked at many times without seeing — with rapture.” - L. S. Lowry

With his iconic ‘matchstick men’, Lowry creates a vibrant moment in Going to Work wherein dozens of workers are dragged along, pulled into the mouths of the factories’ gates like moths to a flame. Throughout the frame there is bustle, and everyone is in motion, and this celebratory stylisation of the crowd, the 'practitioners of the city', provides this great sense of dynamism and movement. In this depiction, Lowry uses his mass of 'pinched figures' to recognise and appreciate the individual worker. This playful approach to his subject is most compelling when set against the drear of an urban scene, a reality that was so often deemed by critics too ugly to be worthy of recreating: a flat landscape of billowing smoke towers, shadowing brick and mortar towers and vignetted, burning skies. In Lowry's development upon this notion of the urban landscape's perceived ugliness, by contrasting the grimly muted skyline with a lively set of figures, finds a distinctly beautiful study of the urban scene. Lowry's transcendentally authentic vision of urbanised life is thus achieved in his adoption of that old Shakespeare line, "What is the city but the people?"

Texture

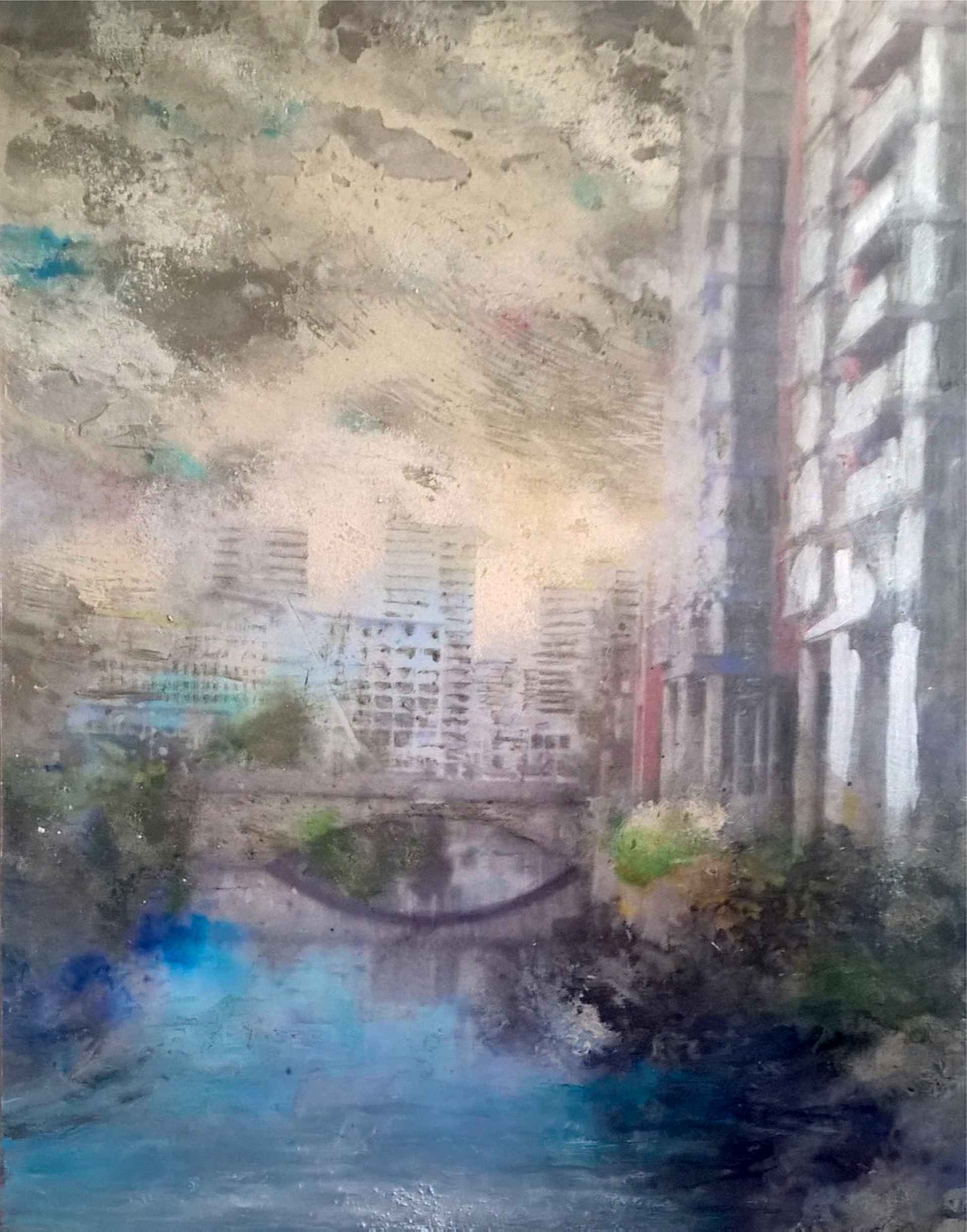

Tim Garner seems to offer something pertinent in his study of the cityscape. As a contemporary urban painter, Garner provides the visceral essence of the city in his haptic engagement. By use of alternative materials and practices, Garner layers the canvas to produce a harsh, jutting surface texture.

In Ancoats Investment Opportunity, we are positioned on the ground, closer to the road and fumes, looking up at the imposing line of buildings that are lit up by a tear in the sky. The scene is dark as we are engrossed in a haze of smog under those blanketing clouds. There is a suffocating dirtiness which is achieved in Garner's vignette of bubbled and scratched paint, acid burns and smeared cement, achieved through a long process of layering protective coatings upon one another. There is a violent feeling in these besmirching features, speaking the violence of an industrial upheaval, with spillover from the street’s cement mixer who rushes through the streets to develop the land. The canvas appears to itself be an object from the scene of industrial development, tattered and dishevelled by industrial progress that is captures.

A postmodern, perceptually generative dialectic of transformation in a culture of uncertainty is captured in this scene. Garner sets out to portray the city streets truthfully, with the implication of grime with his careful process of textural layering, creating what can be read as a powerful and dramatic moment in a eulogy of the city: one of equal parts affection and lamentation.

These artists tell of three wildly different stories of Manchester. In their respective perceptions of the city, we are learned of three unique relationships to the streets. It is in this way that the urban landscape transgresses the factual simplicity of photography and photorealism. To document a city, to see it and represent it faithfully, is to know how it strikes you personally. To find the city scene, one must first see themselves within it.